Basic guide to corruption in the health sector

Corruption in the health sector: A global threat

Corruption threatens universal health coverage and can lead to human rights violations, especially limiting people’s right to a system of health protection. Corruption undermines the ability of health systems to deliver quality healthcare services, adds to inequitable access to services, increases costs for patients, and erodes trust in health systems – resulting ultimately in poor health outcomes.

Although there are different vulnerabilities in high-income countries compared to low-income countries (including the motivations to commit corruption and fraud and the form these take), high-, middle-, and low-income countries are all vulnerable to corruption in the health sector due to common characteristics across all health systems. These include:

- The multitude of public and private actors involved in the health sector, which makes it difficult to monitor their relationships

- The knowledge, information, and power asymmetry between these actors, which gives room for potential abuse of power

- The uncertainty of who will fall ill, when and how, and the uncertainty of health markets (e.g. the supply chain of medicines and medical supplies), which makes it challenging to keep all services and transactions in check

- The large amounts of money flowing through the sector

- The overall complexity of the system, allowing for gaps in accountability and transparency

Corruption is a threat to global health security, as we saw during global health emergencies and outbreaks such as the Covid-19 pandemic, Zika, Ebola, MERS, influenza, and anti-microbial resistance (AMR). For example, corrupt medical regulation practices and supply chain disruptions result in product shortages and an increase in falsified medicines and products. This scenario perpetuates the impending threat of AMR. Moreover, corruption and misinformation during emergencies decrease trust in governance, contributing to citizens’ hesitancy to utilise public healthcare services. This leads to the spread of diseases.

This guide showcases the latest literature and research surrounding what we know drives corruption in the health sector, how it occurs, which groups are the most vulnerable, and what can be done to mitigate corruption risks.

How corruption occurs

Corruption risks include safety risks, operational risks, informational risks, and reputational risks. These are all opportunities that create a fertile context for corruption to emerge. We can identify corruption risks within health systems by looking at health system actors’ interactions and assessing the vulnerabilities to corruption across the World Health Organization’s six key building blocks.

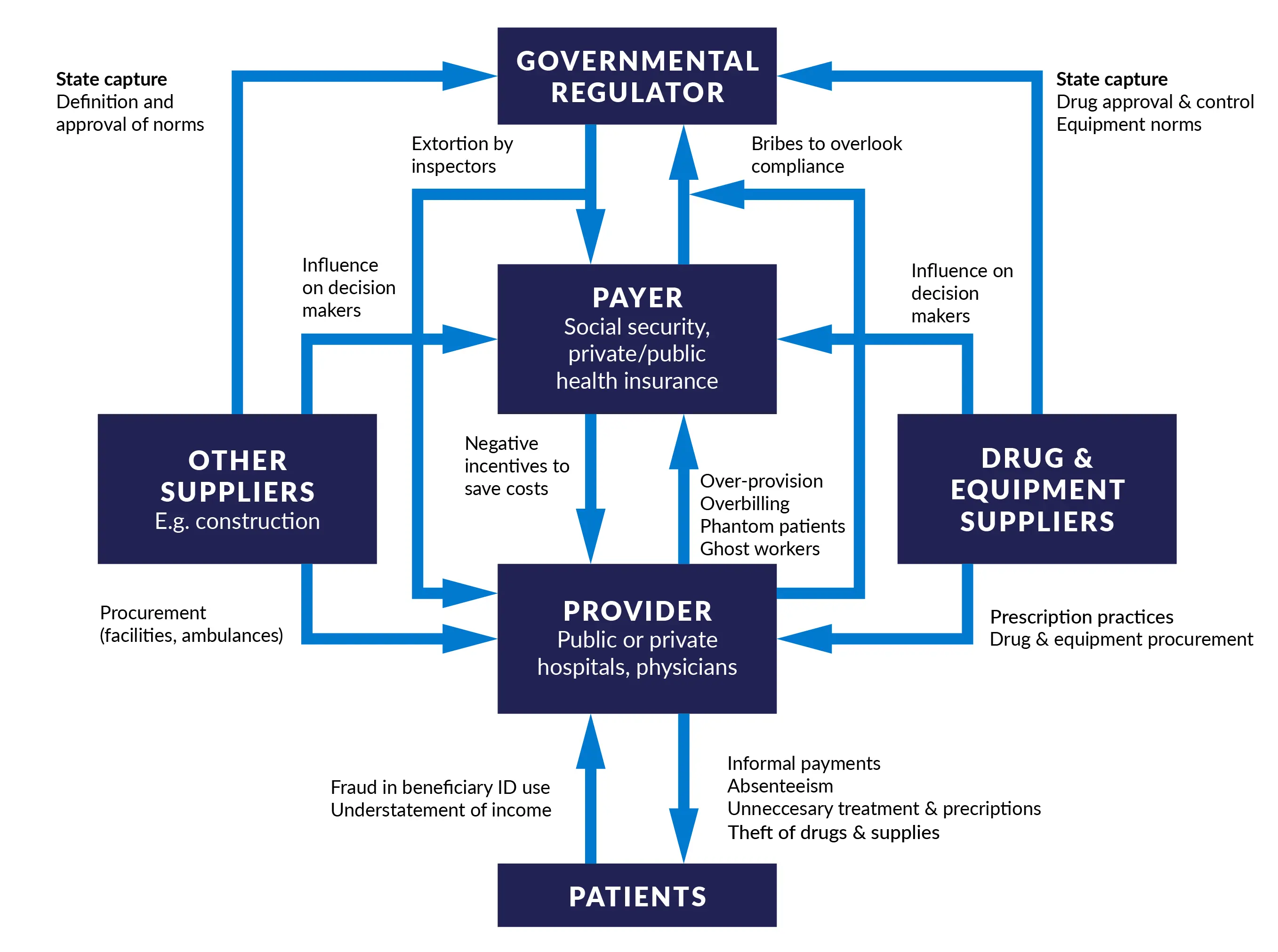

Interactions among health system actors

Patients, providers, payers, government, and suppliers are the five key actors in the health system. They interact in different ways depending on where they are in the system (primary, secondary, or tertiary care) and the diversity of care they provide (e.g. obstetrics, paediatrics, surgical etc).

Figure 1. How corruption takes place among health system actors

Source: Hussmann, K. 2020. Health sector corruption. Practical recommendations for donors. U4 Issue 2020:10.

At the patient level, there is the risk that healthcare users and providers exchange bribes or informal payments so that the users can access care, and sometimes ‘jump the queue’ for faster services.

Providers can also engage in favouritism; private use of public products, equipment, and facilities; dual practice; and absenteeism.

Payers can commit corruption when they misuse government or donor funds, distribute resources based on political influence, or inaccurately charge or pay for services rendered.

Government officials can manipulate the market based on personal and political patronage, provide unwarranted health facility certifications, or fix the bidding process to rig the outcomes of a procurement process of public goods.

Lastly, suppliers can manipulate the procurement process by influencing the preferential selection of a contractor.

The WHO health systems framework

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified six key building blocks of the health system:

- Service delivery

- Human resources for health

- Medicines, vaccines, and technologies

- Health information systems

- Health financing

- Governance

These blocks are interconnected, and it is impossible to disentangle the impact of corruption across them in practice. Nonetheless, this framework helps identify corruption risks affecting health systems, which are quite complex by design.

Service delivery

Corruption at this level includes informal payments or bribes exchanged between patients and providers. A 2020 systematic review of south and south-east Asia literature shows how these occur at every point of patient care, including securing a bed and receiving better or more timely treatment. One study found that over 30% of respondents surveyed from eight African countries reported paying bribes to access healthcare services. In Peru, informal payments were indirectly reported by 10% of health system users surveyed in 2018. This significantly impacts the use of public facilities, with some patients even opting to use the private sector.

Human resources for health

This covers all issues related to the management and policies of human resources, including the health workforce. Corrupt acts include:

- Healthcare worker absenteeism (workers who are on the payroll but are absent without approval)

- Dual practice (providers who are working both in public and private sectors, diverting patients and supplies between the two)

- Ghost workers (real workers knowingly or unknowingly placed on the payroll, or fictitious workers added to the payroll by a dishonest employee who then pockets their wages)

- Patronage

- Clientelism

- Bribe exchanges

- Sextortion

Medicines, vaccines, and technologies

Corruption in this block includes:

- Targeted or improper marketing of goods to providers and patients

- Gift-giving to influence prescription practices or product use

- Marketing of drugs which promotes effects that they do not actually have

- Intentional use of substandard or falsified products

Covid-19 demonstrated the specific impact that substandard or falsified products can have in times of emergencies, as the standard oversight and regulatory mechanisms were overridden for a faster response. This allowed these products to infiltrate the supply chains and exacerbate the spread of the pandemic.

Another significant area of corruption is the procurement of goods and services, which includes bid-rigging and collusion between bidders for contracts. A systematic review from sub-Saharan Africa found that procurement corruption led to frequent stock-outs, substandard drug use (and associated life loss), reduced effectiveness of treatment, lost opportunity costs for companies, and wasted funds. The private sector can play a role in procurement corruption by bid-rigging or paying public officials to select their company for a procurement tender.

Health information systems

These systems ensure the production, analysis, and dissemination of reliable and timely information. Corruption in this block includes the manipulation and misuse of patient data. This can occur in environments that have insufficient local expertise for data management, low data reporting rates, and data reporting inaccuracies. Also the design of the health system can have an influence. For example, systems that operate with pay-for-performance schemes may inadvertently incentivise workers to overbill or run additional tests – as they will receive a financial kickback for more services rendered – and this can occur via data manipulation and misuse.

Health financing

Health financing relates to the adequate use of funds and resources to provide quality, equitable, and efficient healthcare. In a more traditional sense, corruption can include incorrect billing or overbilling for services not rendered. But corruption can also occur in other areas outside of revenue raising, including:

- Pooling of funds – the financial management of paying for healthcare costs for all members

- Purchasing – the allocation of those pooled funds to providers to deliver services

- Benefit design – the decisions surrounding which health services to provide (eg referral systems, co-payments, and waiting lists)

Corrupt acts include the leakage or embezzlement of pooled funds, which affects the purchasing process. The procurement process offers ample opportunities for health financing corruption, including bribing inspectors, improper bidding procedures, and kickbacks for selected tenders. With benefit design, corruption can occur through undue influence and collusion. The pharmaceutical industry may collude with the authorities and influence their decisions as to what products or services are covered by an insurance plan. This flows down to how much a patient may pay for care, or the type of care they receive.

Governance

Leadership and governance includes the strategic policy frameworks, oversight, system design, and accountability of the health system. Illegal – and sometimes legal – lobbying that aims to influence decision-making to advance private interests in the health sector is considered corruption. Weak health system design that leads to poor salaries for health professionals and/or poor accountability frameworks contributes to the existence of informal payments, bribery, and absenteeism at the point of service delivery.

Corruption drivers

Corruption drivers exist in most health systems and can include:

- Poorly managed conflicts of interest

- Weak regulatory and enforcement systems – this can include the lack of sanctions or clear procedures that outline what to do when someone is caught committing corruption

- A significant number of actors involved in managing health systems – from administrators to payers, to supply chain management, and to service workers, which makes national health systems complex, difficult to navigate, and hard to monitor

- Large sums of money running through health systems, creating ample incentives and opportunities for the diversion of funds at every stage

Context is important when identifying drivers. In Nigeria, a study found that service users usually engaged in bribery and informal payments to gain quicker access to health. Poor salaries and weak structures, including low supervision and lack of payment systems, also prompted these forms of corruption.

One way to assess and understand the drivers of corruption is through the application of a political economy analysis (PEA). A PEA specifically considers contextual factors that can help identify drivers more effectively within health system strengthening, and classify the political, economic, social, and cultural factors that influence potential reform.

A study in Ukraine applied a PEA to understand why the country has failed to adopt reforms to its tuberculosis (TB) programme, despite having access to international experts and recommendations on how to do so. The PEA revealed high levels of informal payments and outright corruption. It identified recommendations that would work within the existing political context and dynamics to effect change. It also uncovered the incentives and underlying conditions contributing to the system failings that go beyond just the health system, such as Soviet-legacy incentive structures. The findings informed future TB missions and were shared with the Ministry of Health. This led to the placement of a health governance advisor within the ministry.

Corruption across social and environmental determinants of health

Social and environmental determinants of health – or the non-medical factors such as income, education, employment, air and water quality, climate change, and housing that influence health outcomes – are also impacted by corruption. When funds do not reach the intended destinations in these sectors, it negatively impacts citizens who are already disadvantaged, further exacerbating the impact.

For example, urban planning can be affected by corrupt practices. This leads to inadequate housing and limited housing options, forcing some to pay more or live in poor conditions. Both situations can affect their health by diverting income that needs to be spent on health to cover housing costs, or by putting their health at risk because of unclean or unsafe accommodation.

Corruption, poverty, and food insecurity are also closely related. Corruption makes food insecurity even worse when diverting funds, land, and goods. This can raise the price of food, which then affects those in poverty more if they do not have the ability or means to access affordable food. Also related is access to clean water and sanitation services. Systemic corruption can have a potentially compounding and rippling effect.

Individuals and groups vulnerable to corruption

Corruption also disproportionally impacts vulnerable groups such as those living in poverty or in rural areas, those with disabilities, and women. Discrimination can lead to greater exposure to corruption, resulting in certain groups having a higher negative impact from it. For example, people with disabilities are more exposed to abuse by those who care for them. Embezzlement of funds also occurs when money is diverted from benefit funds for those with disabilities. This prevents them from being able to access assistive devices, reasonable accommodation programmes, and accessibility measures.

When corruption targets people on the basis of age, disability, race, ethnicity, religion, belief, gender, sex or sexual orientation, or other protected characteristics, it is called discriminatory corruption. When a person has compounding factors – such as being young and identifying as female, or being a person with disabilities who identifies as a minority – their risk for corruption may increase.

Informal payments and bribery can affect more disadvantaged groups, as this introduces additional barriers to care, and can compound access issues that those who are less disadvantaged do not have to face (finances, travel distances, discrimination, etc). A study in rural Vietnam found that day-to-day petty corruption can even harm mental health by causing psychological distress.

Women may face more negative impacts of health system corruption, as they interact with the system more because of their childbearing and caretaker roles. A qualitative study in Nigeria of women seeking pregnancy care identified the often fatal and life-threatening impact that corruption has on women in labour when faced with unwarranted or illegal informal payments.

Sexual corruption is another emerging field of gendered corruption research. The are some studies of sexual corruption within health systems, but we lack a full understanding of its impact and how to address it.

Key sector areas at risk of corruption

Procurement in public health systems is particularly vulnerable to corruption because of the potential diversion of limited, life-saving resources. Procurement corruption can occur during all stages of the procurement cycle (setting the bid, selecting the bid, and in bid implementation).

For example, in the UK, a Transparency International report found that 20% of contracts awarded during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 had a red flag of possible corruption, including companies that had political ties or had no history of supplying these products previously. Within the procurement process, there are significant opportunities to make profits, a general lack of accountability, and individuals with discretionary power.

Another aspect of the health system that is particularly vulnerable to corruption is within the production, distribution, regulation, and selling of substandard or falsified medical products. When there are shortages of products caused by substandard or falsified goods, this can flow down to service delivery. Patients may engage in informal payments to access necessary supplies.

As highlighted in a report on corruption in the pharmaceutical sector, corruption often occurs because of weak legislative and regulatory frameworks, undue influence from the manufacturing companies, and a lack of committed leadership from all involved actors aiming to prevent corruption from occurring. During the Covid-19 pandemic, U4 reported on the millions of substandard and falsified medical products that included personal protective equipment, unauthorised anti-viral medications, and Covid-19 diagnostic kits. A study in Colombia also confirmed these findings, highlighting the need to invest in data and monitoring to track the severity of the problem, and create policies and buy-in from key agencies to begin to address it.

Understanding the true impact of big pharma in its undue influence and state capture is also paramount. Notably, the opioid epidemic crisis in the US was found to be manipulated by opioid producers. A 2021 study examined the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on the UK’s All-Party Parliamentary Groups and found evidence of conflicts of interest through payment via drug companies. Research demonstrates that payments to physicians made by pharmaceuticals manufacturers were associated with greater regional prescribing of marketed drugs.

Anti-corruption efforts

Anti-corruption, transparency, and accountability efforts can be broken down into bottom-up and top-down approaches. Bottom-up approaches are led by civil society and often use transparent data and information – also known as community monitoring – to hold government officials accountable. A study from a field experience in community-based monitoring in Uganda found holding officials accountable to the public reduced medicine stock-outs, absenteeism, informal payments, and other abuses of power.

Top-down approaches include the institutional and legislative level of policy and process implementation. As proof of top-down impact and momentum, in 2023 the World Health Assembly renewed its commitment to attaining universal health coverage. Its declaration included language recognising that corruption is a significant barrier to resource mobilisation and allocation and undermines efforts to achieve universal health coverage.

The most promising interventions are those that combine both approaches. Such an example is the open contracting of procurement works. This holds governments accountable by engaging those outside of government (civil society, public, media, and the private sector) via the publication of information on public contracts. The optimal approach is to combine this with: the Open Contracting Data Standard – an international standard that establishes benchmarks for the planning, tendering, awarding, contracting, and implementing stages of procurement; and an integrity pact – an agreement between government and bidders that sets expectations that neither will engage in approach corruption during the process.

Lastly, technological advances are an emerging field of potential solutions. A 2022 systematic review sought to identify technologies specific to pharmaceutical supply chain and procurement optimisation and found four categories of technology solutions: e-procurement and open contracting, track-and-trace technology, anti-counterfeiting technology, and blockchain technology. It also found that these technologies are not being adequately used or leveraged to address anti-corruption efforts. Artificial intelligence (AI) has been proposed as a tool to improve health system governance via intelligence innovations, flexible boundaries, multidimensional analysis, and cognition modification.

An example of successfully applying technology to combat corruption comes from applying blockchain methods to improve medical record management, enhance the insurance claim process, and accelerate clinical and biomedical research. In addition, a study found it could be a solution to safeguarding vaccine distribution during Covid‑19 and potentially applicable to other similar objectives – if there is technical capacity, trust, and political buy-in. The use of these technologies is not a means to an end but should be driven by the specific problems in their contexts after a thorough analysis.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)